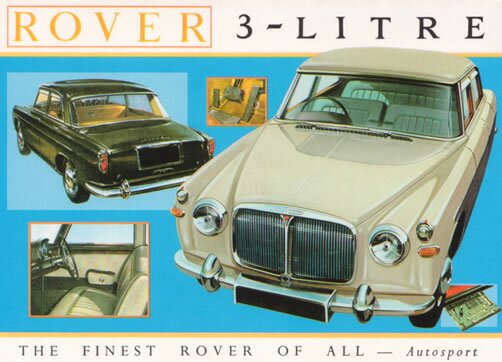

P5 3L: A Gentleman's Club on Wheels

By Kevin Phillips

By 1953 P4 production was well under way, and two new models were under development, ready to be introduced for the 1954 season.

By now it was realised that P4 was going to have a long production run. and as Rover was now going from strength to strength consideration was being given to production of a completely new car.

At this stage Maurice Wilks' thoughts were for a smaller, cheaper car to fit in under the P4, which was fast becoming a huge success. The four cylinder Rover '60' would be released before the end of the year, and thoughts on P5 were for a smaller car also with a four cylinder engine, that was to be some eight inches shorter in length and wheelbase than the P4 cars.

Robert Boyle and Gordon Bashford had formulated ideas on this new car by April of 1953,and it was to weigh no more than 22cwt, and would have what is now known as the 'Base Unit' body construction as appeared later in the P6. Rover had been toying with the idea of base unit construction shortly after the start of the P4 production run, when it was realised just how much weight that solid steel chassis would add to the car, and years before Citroens DS 19 was launched in 1955.

Jack Swaine had been working on a Rover V6 engine design since the 1930s and although prototypes were built they didn't really deliver all that was expected of them. The P3 and P4 T-Head engine design was a development of the V6, but for P5 a completely new engine would be required, either a four cylinder or development would continue further on the V6 design.

Once the decision had been made to develop P5 as a small car, other factors came in to play. It was thought that demand for this new car would be greater than for any previous Rover and the company would lose sales through not being able to produce enough cars. This was because Land Rover sales were going through the roof, and the P4 range had just been expanded, and there were two important new models still on the drawing board.

The company had already been forced to purchase nearly 130,000 square feet of existing factory space in Birmingham, to deal with yet more expansion in Land Rover transmission production, such was the demand for this vehicle. This acquisition had been the fourth such purchase of factory space in as many years.

For a short period Maurice Wilks thought of deferring P5 and developing it as a more versatile car to replace the P4 at a later stage. He quickly realised that Jaguar were having great success in producing and selling their big and fast Mark VII, and that Alvis, Daimler and Armstrong Siddeley were not doing exceptionally well selling cars just that little bit more expensive than the P4. He was prepared to take a gamble that Rover could build a more luxurious car that would compete with Jaguar and steal customers from the likes of Alvis, Daimler and Armstrong Siddeley.

In order to do this P5 would need to be designed by someone with a specialist knowledge in the shaping of cars and the design of interiors. The company's styling office was now developed, and with it Rover's illustrious reputation for designing and producing modern and practical luxury cars would soon be established.

The decision to develop P5 as a larger and more luxurious car that would be aimed at a smaller market meant that it would now be a viable proposition and space could be provided in the existing Solihull factory. Once this decision had been made it was all go, and David Bache was now given the task of shaping the new P5 to Maurice Wilks' wishes.

David Bache had completed an engineering apprenticeship with Austin and had attended Birmingham University and the Birmingham College of Art. He came to Rover at the age of 26 and was given the chance to fulfil his dream to design the best cars in the business. This was in 1955 and the 2.6 Litre '90' was now in production, with the '105' twins in their final development stages.

The 2.6 Litre W engine could not have its stroke lengthened, the only alternative being to enlarge the bore to 77.8mm, which would match the four cylinder '60' and Land Raver engines. To achieve this would require unsatisfactory 'siamesing' between the bores. This had been tried when the original '75' engine was being developed for the Rover '90' but had given problems with overheating between the closely spaced cylinders. Finally Jack Swaine's team were able to re-align the cylinder centres, eventually squeezing 2,995 cc out of the original cylinder block. This was without having to change the overall dimensions, not an easy task as a new seven main bearing crankshaft was also to be incorporated.

The P5 body quickly took shape, the car having a wheel base of 9 foot 2.8 inches which was actually half an inch shorter than on the P4. The car was also 4.5 inches wider and 3.8 inches lower than the P4. The back seat was set closer to the rear axle and the scuttle moved forward which gave an extra eight inches of room inside.

Wrap around front and rear screens were incorporated, with the swivelling quarter windows being dropped in favour of plastic wind deflectors at the top of each side window, as was the practise with the P1, P2 and P3 Rovers.

P5 was designed around a monocoque pressed steel body shell, but was extremely strong due to the addition of a box section chassis sub-frame running from the front of the car back to the front seat area. This sub-frame carried the suspension, steering, engine and gearbox mounts and was located and attached to the body via rubber mounts. The Wishbones and geometry of the front suspension were supplanted by laminated leaf torsion bars that were really long thin leaf springs arranged to twist rather than bend.

This in addition to the substantial development costs of P5, was the reason that production of the 3 Litre Coupe was postponed for another four years. This very smart car with its lowered roof line, rakish front and rear windscreens and distinctive badging had been styled in the mid 1950's by David Bache alongside the original P5 3 Litre.

Initially P5 production was planned to commence during July of 1988, gradually building up over the next few months, with full production being achieved one month before the official launch date of October 1958.

In the event, problems arose due to much of the design and development work running behind schedule, and in order to attempt to reach the deadline, many items for production were signed off before having been tested.

As the production date approached, an inter-union dispute at Pressed Steel delayed deliveries of the first off-tools bodies, the situation now going from bad to worse. There were still some elements of the car's specification that had not been settled, which in turn delayed design of the new assembly lines. As a result the first cars rolled off a temporary production line in the Land Rover assembly plant.

The rush to have the new car ready for the Earles Court Motor Show would prove costly, with the six off-tools prototypes requiring much remedial work to bring them up to a satisfactory standard. There were many problems, one of the biggest being the heavy doors placing too much strain on the body pillars, with the result that cracks appeared in the base of the windscreen support panels.

Rover decided to continue with the planned launch despite some serious problems still not having been resolved. They were convinced that solutions would be found in time to get the car into showrooms shortly after the Earles Court Motor Show. This of course would place immense pressure on the Engineering and Production departments, who already had their work cut out in order to get just two cars ready for the press launch on 22nd 'September, 1958. Managing Director George Farmer had to apologise that no press demonstrator vehicles were available, but those present never new the reason why, or just how much of a struggle it had been to have any cars available at all.

Production of P5 gradually increased and by the end of the 1959/60 year 7,460 cars had been sold compared to 9,670 P4's. The increasing sales justified the huge gamble that Maurice Wilks had taken in the mid 1950's that a bigger, more luxurious car was the way to go. In the event Rover picked up additional sales from people who were more likely to buy a Daimler or Armstrong Siddeley rather than a P4, so they really couldn't go wrong, and of course all the while the Land Rover sales were going ahead in leaps and bounds.

The arrival of Jaguar's new Mark II saloons in 1959 didn't harm Rover sales, and both Alvis and Armstrong Siddeley didn't have sufficient sales to justify the huge expense of updating their ageing models. Armstrang Siddeley finally conceded defeat and dropped out of car manufacture, while Alvis were restricted to production of their two door coupes, until taken over by Raver a few years later. Daimler couldn't hurt Rover either as they were now producing Daimler versions of jaguars, or bigger more expensive limousines. While all of this was good news for Rover, there was concern about just what jaguar were cooking up as a replacement for their Mark IX.

Rover were concerned that the 3 litre would not be abIe to compete with Jaguar's sleek new Mark X, because it simply wasn't fast enough. The original P5 had been cumbersome and heavy, but the option of power steering from September 1960 had helped the handling of the car. The 3 Litre engine only developed 108 bhp, and even in its overdrive form was not a 100 mph car, and could not beat the 'Rover 105' with its 108 bhp and twin carburettors.

One of the continuing problems with the V6 engines that were originally to power the P5 and its successors, was a lack of power, which was put down to a breathing deficiency. The 3 Litre six also suffered in this respect so Maurice Wilks called in one of the acknowledged experts in the field - Harry Weslake. Weslake had been very successful carrying out performance development work for Bentley, and also managed to get remarkable results from the post-war BMC 'A' and 'B' series engines.

The 3 Litre Mark II was released in September 1962 with the new Coupe and revised P4 models 95 and 110. All except the 95 would have an improved engine, incorporating what is referred to as the Weslake Head. In actual fact there was virtually no difference to the cylinder head, the improvement being due to adoption of the P3 design which used a separate inlet manifold. This was more efficient than the integral manifold casting of the original P5 cylinder head design, and allowed a cleaner and less restrictive air flow. This improvement, along with revised gear ratios and a new remote control gear change, which was basically similar to that designed for the P1, transformed the car somewhat, making it more lively. Maximum power went up from 105 bhp to 121 bhp, and maximum speed was now up to just aver 105 mph with improved acceleration to match.

The P5 continued on for the next three years with only minor modifications, but received attention from David Bache's styling team for 1966. The engine was refined still further and with the car's other improvements, the 3 Litre Mark III was created.

This car had slight body changes which really only amounted to attention to the trim, but the interior received new and more comfortable individual seats for both the front and rear passengers. These were larger versions of those fitted to the new P6 2000 that had proved so popular, and gave the 3 Litre the reputation of a 'Gentleman's Club on Wheels'. The P5 was now at the end of its development, and the Mark Ill virtually became a prototype for its successor - the P5B 3.5 Litre Saloon and Coupe.