P4: THE TRUE POST WAR ROVER.

By Kevin Phillips

The P3 should have been ready for release by September 1947 but didn't actually arrive until the following February. These cars were really only a stop gap measure in order to get a somewhat new and improved Rover on the road, while development continued on the true post war new car.

Development of the P4 continued alongside the new Land Rover and although the first plans had only been drawn up in 1946, the car rapidly started to take shape. While mechanically the new P4 was based loosely on P3, the new chassis had already shown up problems that needed to be addressed for the new car.

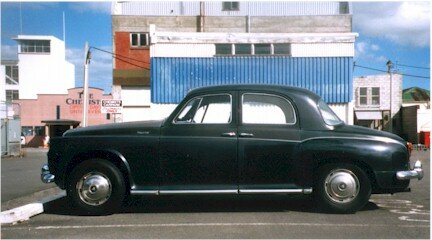

A New Zealand P4 110. Note the P5 hubcaps.

It was already realised that P4 would have a long production life and the Achilles heel of the P3 its chassis frame - would have to be revised. As a result Gordon Bashford laid out a massively strong and heavy chassis frame, with box section side members sweeping over the rear axle. The P3's front suspension had been modified for 1949 and this design, with slight modification, was selected for the new car.

Development moved rapidly ahead resulting in the production life of P3 being limited to less than two years. By October 1949 the new car was all tooled up and ready to go. Pressed Steel would supply the complete body shell from Cowley, tooling for which had cost close to a quarter of a million pounds. The rest of the car would be built at the new Solihull factory with components being supplied from the Tyseley and Acocks Green Factories.

The body style had taken a great deal of development time with Maurice Wilks and Harry Loker settling on a full width body shape. Although this was to be based on the 1947/48 Studebaker cars that Rover had purchased for development purposes, Maurice Wilks had decided to stay with the traditional vertical type of nose and radiator design.

The American influence was quite apparent in the new P4 and showed up in the bench front seat, rectangular instruments and column gear change. The use of light alloy skin panels was inspired by the desire to reduce weight and to economise on the use of sheet steel, which was in extremely short supply. This was a very wise move as the quality of post war sheet steel was extremely poor, having been recycled from the salt laden rust buckets of merchant and royal navy ships that had been rendered obsolete and redundant at the end of the war. Later this decision would pay dividends for Rover, as the products of many other British car manufacturers of the early 1950's suffered quickly from serious rust problems.

The P4 body started life as a clay model instead of a paneled mock-up, which was the traditional way that new Rover models had previously been conceived. One great advantage of this was that it became very easy to make body design alterations as required. The body interior was placed further forward in relation to the road wheels than ever before, so much so that the rear edge of the back door could be cut straight, and barely intruded on the rear wing pressings and did not have to fit around the wheel arch. This also avoided the necessity for the rear wheel arches to intrude upon the car's interior, giving the P4 a far greater amount of interior room than any previous Rover. It also had far more interior space than it's eventual replacement, the P6, in which interior room was sadly lacking even though the two cars had similar body dimensions. The British motoring regulations at the time still required the use of a passing light, and this was incorporated as part of the new grille, being mounted in the centre, which gave the car it's 'Cyclops' designation.

The new car was ready by September 1949, which had been a great achievement considering the amount of new development work that had been required. The P4 was received with mixed feelings by Rover customers, due to it's radically new modern design. Even so there were still plenty of customers for the very few cars that would be made available for the home market. Most cars were being built for export, this being a government directive in order to get the British economy moving again after the war. The price in Britain for the lucky few was 1106 pounds -exactly the same as had been asked for the obsolete P3 75.

There was no four-cylinder version of the new car available at first, only the six cylinder 75 engine being offered which sported a new aluminum cylinder head and a twin choke Solex carburettor. Apart from this the car was mechanically similar to the P3, incorporating virtually the same steering, hydromechanical brakes, gearbox and rear axle design. The P4 driveshaft was now divided incorporating a new centre bearing. The P3 60 engine remained in production but was now dedicated to the new Land Rover, which had already become Solihull's most important single product.

On 28th September 1949, the day that P4 was launched, even Spencer Wilks could have had no idea of just how much this new car was going to mean to the Rover Company. In a short period of time, in conjunction with the Land Rover, it would turn the company into one of the bigger players of the British motor industry.

With Pressed Steel supplying complete body shells, Rover geared up more towards quantity production. The first financial year - 1949/50 - saw only 3,563 P4's built which was a considerable drop on P3's final production year. The 1950/51 year saw 8,821 P4's built, but it wasn't until 1953/54 that the prewar record was finally broken, with 11,991 cars being produced.

For the first nine years of production the P4's would be the only private cars built by Rover, and they would be steadily improved and updated over their long production life. There were only two significant styling changes, with most of the body pressings being the same in 1964 as they had been back in 1949, when Pressed Steel had been given the original tooling order.

The front of the car was revised in March 1952 with the 'Cyclops' grille being dropped in favour of a plain but neatly proportioned grille with vertical bars. This grille would continue on to be incorporated into the future P5 models, and would many years later become the Rover marque insignia that would be fitted to all future Rover cars. The front was revised again in September 1956 when the lines of the front wings were raised, the direction indicator units being incorporated into the top front of each guard. October 1954 saw the rear of the car revised with the tail being restyled to a smarter less sloping line, and a completely new large semi wrap around rear window being installed. This improved the rear visibility as well as the looks of the car, and gave a much larger carrying capacity for the luggage boot. The final major re-style came in September 1958 when the radiator grille was revised, gaining recessed bars with a prominent centre one. New style bumpers were fitted, a chrome shroud was added to the rear number plate housing and the wooden facia rail of the dash received a padded roll at the top.

Originally when the P4 was launched only one model was available, due to the supply restrictions that were in force at the time. The car had been designed to the same formula as Rover~ s products of the 1930's, when they were able to market several different models ranging from 10 HP to 20 HP, all using the same basic chassis frame. Once the supply restrictions had been lifted, P4 was developed in much the same way.

Two new models were released for the 1954 model year, the four cylinder '60' and the six cylinder '90'. Their engines were developments of the original '75' engine that had been designed for the P3. The '60' engine was a much modified and over bored version of the 1595 cc P3 unit that was being fitted to the Land Rover. Repositioning the cylinder bores had allowed an increase in their diameter, and coupled to a new aluminium cylinder head with integral manifolding and an SU carburettor, the engine now had an increased capacity of 1997 cc.

The '90' engine was an over bored '75' engine block with repositioned cylinders, a single SU carburettor and a capacity of 2638 cc. For 1955 the '75' engine was revised and became a short stroke version of the '90' engine, having its original capacity increased to 2230 cc and using a single SU carburettor. 1956 brought the option of servo-assisted brakes and a Laycock De Normanville overdrive unit for '90' models. The Rover freewheel device was still standard equipment but was not available on the servo assisted cars, this being to ensure there was engine braking available in the unlikely event that the servo assistance feature should fail.

For 1957 two new cars joined the range, the '105 R' and '105 S' twins. The 'R' stood for 'Roverdrive', and comprised a '90' engine block with a brand new twin carburettor aluminium cylinder head giving 108 bhp, with a semi automatic transmission. The '5' stood for 'Sporting', and was a tuned up version of the '90' engine the same as the 'R', but with manual transmission and overdrive fitted as standard equipment. The 105 5' quickly became the top of the range model, and was fitted with the majority of optional extras as standard equipment. These were particularly smart cars, especially when finished in the new two-tone colour schemes that were introduced for the 1958 model year.

The '105 R' was Rover's first attempt at building a car fitted with automatic transmission, and while it worked well in service and was particularly smooth, there could be problems with the complicated array of control linkages if not set up and adjusted correctly. The torque converter was somewhat inefficient and soaked up more engine power than was anticipated, resulting in the car having similar performance to the four cylinder '60' model, and heavy fuel consumption. While many owners adored this car it did not fare well in Britain, with the majority of cars being produced for export, many coming to New Zealand but a majority finding homes in Australia where they became quite popular.

The 1959 model year saw the release of the new P5 3 Litre and the '105 R' was dropped altogether. The '105 5' continued in production but was re-designated '105', and the freewheel option was no longer available on the '90'. This was to be the last year that freewheel would be available and it would disappear altogether at the end of the season when the '60' and '75' models ceased production.

The P4 range was completely revised for 1960 when the new 3 Litre had been in production for a year. In order to standardise on engines and parts supply, the entire P4 range was dropped and two new models appeared, the '80' and '100'. The Rover '80' replaced the '60', and used the conventional overhead valve four cylinder 2286 cc engine as designed for the Series 2 Land Rover. The '100' replaced the '75' and '90' models, it's engine being a development of that designed for the new 3 Litre. This engine had seven main bearings in place of the original four and a capacity of 2625 cc, developing 104 bhp. Apart for the very first and some export models, all Rover '80' and '100' cars were fitted with overdrive as standard, and all had Girling disc brakes at the front.

This was to be the final development stage of the P4 range, as by early 1962 the new P6, which was to become the future Rover 2000, was entering it's final development phase. However due to circumstances beyond their control, Rover had to revise the release date for P5 which meant that P4 would need to continue in production for at least another two years.

September 1962 saw release of the Mk 2 3 Litre, and with it two new P4 models, the '95' and '110'. These cars were fitted with the smart new instrument panel of the Mk 2 3 Litre, and apart from the very first cars, lost the traditional P4 aluminium doors, bonnet and boot lid, these panels being replaced with mild steel. The Rover '95' replaced the '80' but retained the '100' engine, although it was slightly detuned, developing 102 bhp.

The new Mk 2 3 Litre engine was a great improvement on the original due to a new cylinder head with a separate inlet manifold. This had been designed by Harry Weslake, a breathing and performance engineer, famous for his work with Bentley cars. His transformation of the 3 Litre engine was excellent, and it was decided to marry this new cylinder head to the '100' engine block. This new engine was fitted to the '110' and developed 123 bhp, being in effect a short stroke version of the 3 Litre engine. Apart from the engine these two P4's were virtually the same, the '110' having a slightly higher specification, although this only amounted to the addition of overdrive, an electric windscreen washer and the 3 Litre type hubcaps. These new P4's were to remain in production until well after the release of the new P6 Rover 2000, and were slightly refined towards the end of production with the last cars receiving some P6 spec equipment.

The new P6 was released in September 1963 and for the next eight months Rover were producing P4, P5 and P6 models simultaneously, almost side by side. During this period Mk 2 versions of the '95' and '110' had been developed as a backup new model should the public not be willing to accept the radically new concept of P6. In practice the P6 was an unqualified success with demand far outweighing production.

Within six months it was clear that the Mk 2 '95' and '110' would now not need to go into production, and component manufacture for P4 finished shortly thereafter. The final P4 cars were produced in May 1964, with the very last P4, a Rover '95' rolling off the production line on 27th May, 1964. This was the very last of 130,342 P4's that had been built since 1949.

Unfortunately Rover were so involved with their new baby, the P6, that little attention was paid to this car apart from the traditional 'end of line' photograph. In fact Rover were so lax that it is fairly certain that the car that appeared in the 'end of line' photograph wasn't even the final P4 to be built. This was car number 760-03297,and was finished in Charcoal. The P4's did not always come down the production lines in chassis number order, but they did run numerically in line number order. The final P4 was Line Number 1091, a 95 with chassis number 760-03293, finished in Burgundy. These last P4's were sold off like all other new cars, their significance not being realised until far too late. Unfortunately both these historic Rover P4's have now long since driven into oblivion.